What Is a Buffer?

A Foundational Concept in Computer Memory and Data Flow

If you’ve ever watched a video online and seen it pause to “buffer,” or worked with low-level programming languages that require precise memory management, then you’ve brushed up against a concept that underpins virtually every digital experience: the buffer.

A buffer may sound like a technical buzzword, but at its core, it’s a simple and ingenious solution to a universal problem in computing—mismatched data flow. Whether it’s a keyboard input, network stream, file I/O, or audio processing, buffers are the invisible stabilizers that prevent chaos in your digital world.

In this article, we’ll break down what a buffer is, why it’s necessary, how it works under the hood, and where it appears in software, hardware, and real-time systems. Think of this as your comprehensive field guide to one of computing’s most underrated power tools.

What Is a Buffer?

In computer science, a buffer is a temporary memory area used to store data while it is being moved from one place to another. This is usually done when there’s a speed mismatch between the data producer and the data consumer.

One-line definition:

A buffer is a reserved region of memory that temporarily holds data to handle timing mismatches between producers and consumers.

Buffers smooth out data flow, enabling asynchronous communication between components that don’t operate at the same speed or on the same timing schedule.

Real-World Analogy: The Waiting Room

Imagine a doctor’s office. Patients (data) arrive faster than the doctor (processor) can see them. So they wait in a waiting room (buffer). If the doctor sees patients quickly, the waiting room stays mostly empty. If not, it fills up—and eventually, some patients might have to leave (data loss).

In digital systems, buffers are the waiting rooms for data.

Why Buffers Exist: The Problem of Mismatched Speeds

Here are some typical mismatches:

- CPU vs. Hard Disk

- Network input vs. Video decoder

- Keyboard typing vs. App processing input

- Audio stream vs. Audio output hardware

Without buffers, data would either:

- Overflow (lost data if incoming is too fast)

- Underflow (starved output if incoming is too slow)

Common Use Cases of Buffers

| Domain | Example Use of Buffer |

|---|---|

| Networking | TCP/IP packet buffering before processing |

| Multimedia | Video/audio preloading to prevent stuttering |

| Operating Systems | Keyboard input stored in input buffer |

| I/O Operations | Buffered file writing and reading |

| Hardware | GPU command buffers or disk write caches |

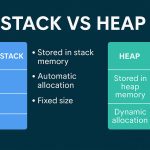

Buffer vs Cache: What’s the Difference?

These two terms are often confused.

| Feature | Buffer | Cache |

|---|---|---|

| Purpose | Temporarily hold data in transit | Store copies of frequently used data |

| Read/Write | Mostly write-first | Mostly read-first |

| Time-sensitive | Yes | No |

| Examples | Video buffering, audio stream | CPU cache, browser cache |

Think: buffer = traffic light, cache = shortcut road.

Types of Buffers

1. Input Buffer

Used when data is received from an external source (keyboard, sensor, etc.)

2. Output Buffer

Stores outgoing data until the destination is ready (printer, display, network).

3. Circular Buffer (Ring Buffer)

- A fixed-size buffer where the end wraps around to the beginning.

- Efficient for streaming or FIFO operations.

4. Double Buffering

- Two buffers used alternately.

- One is filled while the other is being processed.

- Prevents screen tearing in graphics rendering.

Buffer in Programming Languages

In C/C++:

You often define a buffer manually:

char buffer[1024];

fgets(buffer, 1024, stdin);In Python:

Buffers are mostly abstracted, but can be accessed via io module:

import io

buffer = io.StringIO()

buffer.write("Hello, buffer!")

print(buffer.getvalue())In JavaScript (Node.js):

const buf = Buffer.from('Hello World');

console.log(buf.toString()); // Output: Hello WorldBuffer Overflow: When Things Go Wrong

A buffer overflow happens when a program writes more data to a buffer than it can hold. This overwrites adjacent memory and can lead to:

- Data corruption

- Crashes

- Security vulnerabilities

Famous Example:

The Morris Worm (1988) used buffer overflows to infect machines. Even today, many cyberattacks exploit improperly managed buffers.

Copy-Paste Formulas: Buffer Metrics

1. Buffer Fill Level (%)

Buffer Fill Level = (Current Data Size / Total Buffer Size) * 100Example:

If buffer size = 2048 bytes and 1024 bytes are filled:

Fill Level = (1024 / 2048) * 100 = 50%Operating System Buffering: Standard I/O

In languages like C, standard streams (stdin, stdout, stderr) are buffered by default.

Example:

printf("Hello"); // Might not appear immediately

fflush(stdout); // Forces the buffer to flushThere are 3 types of buffering:

- Fully Buffered (e.g., files)

- Line Buffered (e.g., terminal)

- Unbuffered (e.g., stderr)

Buffers in Multimedia: Smooth Playback

In streaming apps like YouTube or Spotify:

- Data is preloaded into a buffer

- Playback reads from buffer, not directly from the network

- If network drops, the buffer helps keep playback smooth

This is the loading circle we often call “buffering”.

Network Buffers: Hidden but Critical

Network interfaces (NICs) and operating systems use buffers to:

- Absorb incoming packets before processing

- Temporarily hold outbound data

If the buffer is too small:

- You risk packet drops

If too large:

- You introduce latency (known as bufferbloat)

Key Metric: Buffer Size vs Bandwidth Delay Product (BDP)

BDP = Bandwidth * Round Trip Time (RTT)This helps determine optimal buffer size for network performance.

Circular Buffers: Efficient and Elegant

Circular (ring) buffers use:

- A fixed-size array

- A head and tail pointer

- Wraparound logic

They’re fast, memory-efficient, and used in:

- Audio processing

- Real-time systems

- Embedded systems

Example Python Implementation:

class CircularBuffer:

def __init__(self, size):

self.buffer = [None] * size

self.head = self.tail = 0

self.size = size

self.full = False

def write(self, data):

self.buffer[self.head] = data

self.head = (self.head + 1) % self.size

if self.full:

self.tail = (self.tail + 1) % self.size

self.full = self.head == self.tail

def read(self):

if self.head == self.tail and not self.full:

return None # buffer empty

data = self.buffer[self.tail]

self.tail = (self.tail + 1) % self.size

self.full = False

return dataBuffers in Graphics: Double and Triple Buffering

Used in GPU rendering:

- Prevents tearing and stuttering

- One buffer is displayed while another is drawn into

- Triple buffering adds a third buffer for even smoother transitions

Buffers in Embedded Systems

In real-time embedded systems:

- Timing is critical

- Interrupts write to buffers

- Main program reads from them

Example: UART Serial Communication

Incoming bytes from a sensor are written to a buffer and read when the CPU is ready.

Best Practices for Buffer Management

- Always check size limits to prevent overflows.

- Use safe string handling (e.g.,

strncpyinstead ofstrcpyin C). - Flush buffers when needed to avoid stale data.

- Monitor buffer fill levels in performance-critical systems.

- In streaming apps, pre-buffer enough data to survive brief interruptions.

Conclusion: Why Buffers Matter Everywhere

From video games to network routers, from your keyboard to the cloud, buffers are everywhere. They might seem like just memory placeholders, but they’re what allow computers to multitask, stream, render, and communicate with incredible reliability.

Think of them as the unsung heroes that absorb digital chaos—and make order out of it.

Related Keywords:

Audio Buffer

Buffer Overflow

Circular Buffer

Data Stream

Double Buffering

Input Buffer

Line Buffering

Memory Allocation

Output Buffer

Ring Buffer

Standard I O

Streaming Buffer

TCP Buffer

Temporary Memory